Originally published in Junkee.com 2/2/2015

By Liam McLoughlin 15/2/2015

In 2006, French man Ilan Halimi was kidnapped in Paris by a group named the Gang of Barbarians. For 24 days he was held in an apartment block and beaten, stabbed and burned. Dozens of neighbours heard the commotion; many came to watch, some even joined in. No one called the police. Halimi was later found in a forest outside Paris with acid and gasoline burns to 80% of his body.

It was a shocking example of what psychologists call the bystander effect; the more people present when someone is in distress, the less likely anyone is to help. There have been decades of research into the effect since the infamous murder of Kitty Genovese outside her apartment block in Queens in 1964. This murder was also seen by several neighbours, who waited 30 minutes to call the police.

Researchers have found good reasons for the bystander effect, and love using jargon to explain them.

The first is “pluralistic ignorance”, a kind of conformity which prevents us from seeing a situation as an emergency which compels action. We look to others for our social cues in these situations, see passivity, and respond similarly.

The second term is “diffusion of responsibility”. More witnesses mean people feel less personally responsible. Total inaction can often be the result, as in the tragic cases of Halimi and Genovese.

The bystander effect is also used to discuss systemic political tragedies. The most infamous of these has been the Holocaust, but it has also been applied to the murder of Indigenous peoples and civil rights workers in the US. Can studies of the bystander effect help explain the ongoing collective indifference of the Australian public to the brutal treatment of asylum seekers? And if so, how can we overcome it?

Human Rights and Human Responses

The bipartisan consensus in Australian politics over the last fifteen years has been to punish people who have done nothing more than exercise their right to seek asylum under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. In late 2014, the new UN High Commissioner for Human Rights condemned Australia for a “chain of human rights violations”, while the UN Committee on Torture warned that the conditions at detention facilities on Nauru and Manus Island are causing significant physical and psychological harm. Yet in the face of the imprisonment of innocent children and adults, an epidemic of mental illness, self-harm, murder, hunger strikes and suicide, the bulk of the public remains unmoved.

The muted public response to the most recent events on Manus Island confirms the picture. Australians are not beating down the doors of our local members. We are not flooding the streets in mass demonstrations. In fact, a poll from July 2014 found 36% of Australians thought the government was taking the right approach to asylum seekers, while only 27% thought it was too tough.

There are many exceptions. The Refugee Action Coalition, the Refugee Advocacy Network, the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre and the Refugee Council of Australia have been shining lights in the NGO sector. There are occasional outbursts of public action (such as the protest held during the Australian Open this weekend), social media periodically trembles with outrage about refugee policy, and The Guardian Australia has offered consistent coverage of the plight of asylum seekers. Yet the major parties continue their punitive approach, and the Australian mainstream falls into line. For the most part, Australia is a nation of bystanders.

In this case, the ordinary bystander effect has been multiplied by the distance most Australians are from the scene of the crime, and by the millions of people who are aware of what’s going on. There is “pluralistic ignorance”, as we see our friends and families going about their daily routines and think, ’What human rights abuses?’ There is “diffused responsibility”, as we look to our political leaders and a smorgasbord of activist NGOs and think, ‘If it’s really so bad, they will fix it’.

Our national apathy is in one sense an understandable consequence of universal psychological processes.

It is also something more sinister.

Abbott and Friends Exploit the Dark Side of Human Psychology

One critical factor determining whether a bystander will intervene is their perception of how similar they are to the victim. In their report on the motivations and actions of bystanders, the Australian Human Rights Commission found that “when an observer identifies with the target this increases the likelihood that an event will be noticed and perceived as an injustice”. Intuition will tell you as much: people are more likely to help others in their “in-group”; You are more likely to help a friend in need than a stranger.

In the case of strangers though, research shows increased willingness to intervene if you share the same language or ethnicity. In one study, white Americans took twice as long to help African-Americans, compared to those who looked like them. This became a matter of public debate in China last year, when passengers on a Shanghai train fled the carriage after a white male fainted. Perhaps if all asylum seekers looked like Schapelle Corby, we would not be in this mess.

It is this factor that the Abbott government has manipulated to help maintain the silence and complicity of the Australian public.

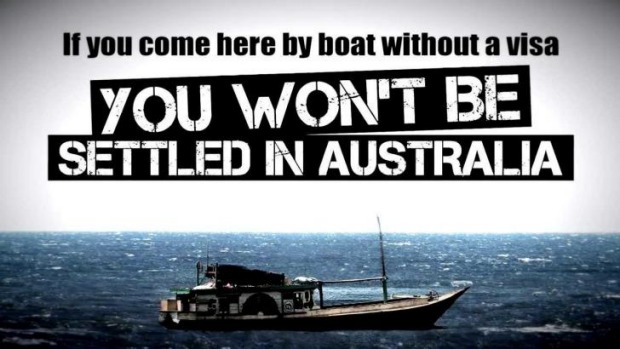

In their campaign to draw battlelines between the Team White Australia in-group and the asylum seeker out-group, Abbott, Morrison, Dutton and Co appeal to some pretty deep, dark aspects of human behaviour. The government is already blessed with the natural advantages of plural ignorance, and diffused responsibility, as well as pre-existing differences in language and ethnicity. It then radicalises these differences by portraying asylum seekers as criminals who do not deserve our empathy.

You hear it in the language of “illegals”, “stop the boats”, “border security”, “non-compliance” and “disruptive behaviour”, and see it in the use of tactics like riot police, and solitary confinement. They also combat attempts to humanise asylum seekers by controlling information, a practice that ranges from restricting press access, to secrecy surrounding “Operation Sovereign Borders”, to blatant deception.

Standing Up For Asylum Seekers

Contrary to all of the tabs you might have open now, it’s not all dreadful news. There’s more and more research on how to overcome the bystander effect – work which could help refugee campaigners and journalists in their efforts to convert passive bystanders into active citizens.

Psychologists tell us that the antidote to “pluralised ignorance” is being clear about the nature of the emergency. Recent stories about hunger strikes on Manus Island and in Darwin will alert some Australians to the critical condition of many asylum seekers. The passive conformity that goes hand-in-hand with the bystander effect is also weakened when people see others helping. This principle makes the work of the Refugee Action Coalition and the Asylum Seekers Resource Centre even more vital.

The balm for “diffused responsibility”, meanwhile, could be direct and personal appeals. For example, victims in distress are advised to say things like, “You in the green jumper, please help me and call 000”. The Guardian recently obtained audio of a desperate asylum seeker detained on Manus Island, crying out “we are human beings… Please help us. Please help.” to the Australian people; it was a potent moment. Because we the people are directly addressed, it is harder to shirk responsibility; harder to stay passive.

The more personal the appeal is, the higher the chance of success. Directing a series of letters, audio or film clips from individual asylum seekers to prominent Australians may be effective. A mass of personalised letters from citizens to influential leaders, on behalf of individual asylum seekers, could help too. Social media and viral marketing campaigns may also use targeted appeals to spark action.

Bystander education is another important way to overcome inaction. Training programs have been used successfully to minimise the bystander effect in cases of sexual assault. Research in Victoria from 2011 found that less than 30% of people would act if they witnessed racism. Currently the Human Rights Commission is conducting a national bystander anti-racism campaign called “Racism. It Stops with Me” to increase these numbers. A national NGO campaign like this for asylum seekers could go a long way to taming the effect of government propaganda which polarises Australians and asylum seekers and criminalises innocent people.

We could also empower citizens with the belief that their actions matter, and give them clear ways to engage. This means dispelling the myth that, apart from the walk to your local school every three years, democracy exists only on TV. It means publicising the many ways to act, whether joining your local Refugee advocacy group, going to the next refugee rally or forum, writing articles or filming documentaries about the issue, organising a chat with your local member, or inventing your own mode of creative protest.

Researchers have also found that people are less likely to turn a blind eye to a victim if they are first exposed to an inclusive group identity. In one experiment, participants primed with the concept of “Manchester United football fans” offered less and slower help to fans from a rival team. When primed with the more inclusive term “football fan”, people offered help equally to everybody.

If Australia’s political leaders communicated a broad group identity of diverse nations, languages, religions and ethnicities, instead of an identity based on the Neighbours cast, circa 1986, the death of Reza Berati would have been unthinkable.

If our government spoke of human beings instead of criminals, offshore processing, turning back boats, children in detention and indefinite imprisonment for all would be unbearable.

Confronted with this spectacle of suffering, we would refuse to just stand by and watch.