Originally published in New Matilda 25/05/2016

By Liam McLoughlin 25/05/2016

Behind the risible Minister's hapless racism is the kind of evil Hannah Arendt once grappled with, writes Liam McLoughlin.

“The trouble with Eichmann was precisely that so many were like him, and that the many were neither perverted nor sadistic, that they were, and still are, terribly and terrifyingly normal. From the viewpoint of our legal institutions and of our moral standards of judgment, this normality was much more terrifying than all the atrocities put together.” -Hannah Arendt

Over the weekend New Matilda published Dr David Berger’s articulate and heartfelt case for comparing elements of Australian asylum seeker policy with aspects of Nazi Germany. Dr Berger highlights similarities in the rhetoric, secrecy, scapegoating, and concentration camps used by both regimes.

He points to the dismal truth about how governments can get away with murder.

“There is the real lesson the Nazis have taught us, the lesson we must draw on every day in 2016 if the gruesome experiences of 1933-1945 are to teach us anything from history: if you tell a big enough lie, a lie so far out of the experience of ordinary people that they cannot comprehend it, if you tell them that you are doing nothing more than keeping them safe, if you tell them that desperate times require desperate measures and if you do your utmost to conceal from them the unpleasant reality of what you are actually doing, then eventually you will find you can get away with absolutely anything, even the industrialised killing of millions of people.”

Though such comparisons are unthinkingly dismissed in some quarters, they have a simple but important point: understanding past evil can help illuminate present evil.

Hannah Arendt’s Theories Of Evil

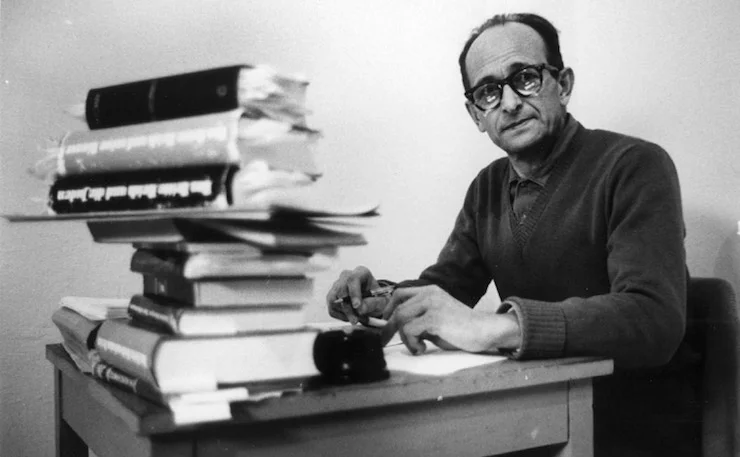

There is no more significant theorist of industrialised evil than Hannah Arendt and no more relevant conception than in her 1963 book, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. The German-American political theorist travelled to Jerusalem in 1961 to report on the trial of Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann for the New Yorker. What she learned about the man who managed the mass deportation of Jews to ghettos and extermination camps resonates in Australia in 2016.

According to Associate Professor Peter Burdon and others writing in the Adelaide Law Review, Arendt’s understanding of evil changed over the course of this trial. In her 1951 book, The Origins of Totalitarianism, Arendt argued for such a thing as ‘radical evil’, where evil motive or intent is present. Observing Eichmann a decade later, she began to think a more prosaic kind of evil was far more dominant.

In an interview for an Against the Grain podcast, Burdon describes Arendt’s first impressions of Eichmann.

“When she arrives at the trial, she is struck by this buffoon. This ordinary, banal bureaucrat, who…can only seem to communicate properly in officialese, has a complete inability to be critically reflective or to think about moral questions. Fundamentally she is struck by his ordinariness.”

She saw him as more thoughtless than wicked, writing “the longer one listened to him, the more obvious it became that his inability to speak was closely connected with an inability to think, namely to think from the standpoint of someone else.” Arendt witnessed a man more foolish than sadistic: “Despite all the efforts of the prosecution, everybody could see that this man was not a “monster”, but it was difficult indeed not to suspect that he was a clown.”

Instead of perceiving some inner malevolence, Arendt believed Eichmann was simply unable to ask himself an essential moral question: could I live with myself if I take this action?

Arendt argued that Eichmann’s thoughtless evil, his discounting of the monstrous acts for which he was responsible, was enabled by language: “Clichés, stock phrases, adherence to conventional, standardized codes of expression and conduct have the socially recognized function of protecting us against reality”.

One such example was this bold declaration of peacemaking during the trial.

“Now, he proceeded, he “would like to find peace with [his]former enemies” – a sentiment he shared not only with Himmler…but also, unbelievably, with many ordinary Germans, who were heard to express themselves in exactly the same terms at the end of the war. This outrageous cliché was no longer issued to them from above, it was a self-fabricated stock phrase, as devoid of reality as those clichés by which the people had lived for twelve years…Eichmann’s mind was filled to the brim with such sentences.”

The Spreading Fungus

Now with all this discussion of buffoons, clowns, paucity of critical reflection, moral vacuity and the unthinking recitation of clichés, no doubt your mind has raced to Peter Dutton. So it should, especially after a quick glance at his record as Immigration Minister.

Yet let’s not let Dutton’s spectacularly awful reign obscure names like Ruddock, Howard, Burke, Rudd, Morrison, Abbott and Turnbull on the rollcall of perpetrators of thoughtless evil.

Arendt’s reflections help us understand not only the psychic contortions of the individuals responsible for Australia’s crimes against humanity, but also how these contortions then permeate the rest of society.

Author Elisabeth Young-Bruehl described the process in a 2011 article for the Guardian.

“True villains and true psychopaths are, fortunately, rather rare; but, in the right circumstances, becoming unfeelingly obedient and inhuman in this way can become a common condition. When political life atrophies and debate and questioning cease, while thoughtful moral experience is blocked internally, the resulting capacity for evil can spread like an epidemic. Before she went to Jerusalem, Arendt had feared that thoughtlessness – “the headless recklessness or hopeless confusion or complacent repetition of ‘truths’ which have become trivial and empty”, as she described it in The Human Condition (1958) – had become “among the outstanding characteristics of our time”.”

Suddenly Malcolm Turnbull’s description of Dutton as “outstanding” makes much more sense.

Here is a description which appears almost tailor-made for the Australian asylum seeker ‘debate’ between the major parties – unfeeling obedience to the party line, inhumanity, the atrophy of political life, the cessation of thoughtful moral questioning, the complacent repetition of empty ‘truths’.

Arendt warned that thoughtless evil “can overgrow and lay waste to the entire world precisely because it spreads like a fungus”.

It was this fungus which spread throughout Nazi Germany. Eichmann’s failings to critically reflect on moral questions, to believe and recite the lies of the regime, were the same failings which infected German culture as a whole.

“German society of eighty million people had been shielded against reality and factuality by exactly the same means, the same self-deception, lies, and stupidity that had now become ingrained in Eichmann’s mentality. These lies changed from year to year, and they frequently contradicted each other…but the practice of self-deception had become so common, almost a moral prerequisite for survival, that even now, eighteen years after the collapse of the Nazi regime…it is sometimes difficult not to believe that mendacity has become an integral part of the German national character.”

It’s difficult to deny this conclusion when you examine popular attitudes of the time.

“The overwhelming majority of the German people believed in Hitler – even after the attack on Russia and the feared war on two fronts, even after the United States entered the war, indeed even after Stalingrad, the defection of Italy, and the landings in France.”

Arendt tells us that Nazi Germany managed to normalise evil: “In the Third Reich evil lost its distinctive characteristic by which most people had until then recognised it. The Nazis redefined it as a civil norm.”

Philosopher Judith Butler articulates this normalisation of evil well in a piece for the Guardian.

“If a crime against humanity had become in some sense “banal” it was precisely because it was committed in a daily way, systematically, without being adequately named and opposed. In a sense, by calling a crime against humanity “banal”, she was trying to point to the way in which the crime had become for the criminals accepted, routinised, and implemented without moral revulsion and political indignation and resistance.”

No derisive invocation of Godwin’s Law can dispel the obvious parallels with Australian society today. Despite the best efforts of our governments, fifteen years of human rights abuses in offshore concentration camps are no secret. We stand condemned by the UN and the whole world knows our crimes.

Yet in the Australian context, barring notable exceptions like the refugee movement and the Greens, these crimes are “accepted, routinised and implemented without moral revulsion and political indignation and resistance”.

The vast majority of Australians believe the Federal Government’s propaganda. They have ceased to ask themselves vital moral questions and instead swallow official lies about queues, illegals, and border protection.

A notorious poll during the dark ages of Tony Abbott’s rule found 60 per cent of Australians wanted to “increase the severity of the treatment of asylum seekers”. Though this may have softened in the context of the Let Them Stay campaign, both major parties remain convinced cruelty is a vote winner.

The majority of Australians have succumbed to the spreading fungus of thoughtless evil. To paraphrase Arendt, it is sometimes difficult not to believe that mendacity has become an integral part of the Australian national character.

Opposing Thoughtless Evil

We learn from Arendt that, despite appearances, Peter Dutton is not the main problem.

The fundamental issue is the systemic infection of our political system and civil society with thoughtless evil.

While Dutton is a particularly heinous example of such evil, so too were Morrison and Ruddock. In the current political climate, Peter Dutton is in fact “terribly and terrifyingly normal”. In a system which fosters uncritical self-deception, there will always be another Peter Dutton.

For Arendt, taking time to think critically is our best defence against thoughtless evil.

Judith Butler discussed this remedy in the same Guardian piece.

“If Arendt thought existing notions of legal intention and national criminal courts were inadequate to the task of grasping and adjudicating Nazi crimes, it was also because she thought that Nazism performed an assault against thinking. Her view at once aggrandised the place and role of philosophy in the adjudication of genocide and called for a new mode of political and legal reflection that she believed would safeguard both thinking and the rights of an open-ended plural global population to protection against destruction.

What had become banal – and astonishingly so – was the failure to think. Indeed, at one point the failure to think is precisely the name of the crime that Eichmann commits. We might think at first that this is a scandalous way to describe his horrendous crime, but for Arendt the consequence of non-thinking is genocidal, or certainly can be.”

The task for Australian society is to think critically about our refugee policies.

Failure to do so will lead to even darker times for our nation.