Not technically Mario Kart. Wario Kart Wii by Thiago Borbolla/cc

By Liam McLoughlin 4/2/14

The climate change debate is more futile than trying to sell hearing aids over the phone. On one side we have the nice people who read books and sing in the local choir, who use phrases like “97% of scientists”, “4 to 6 degrees of warming”, “civilisational collapse” blah blah blah SHUT UP ABOUT IT. On the other we have confused elderly men vomiting what can only be described as English words, such as “global warming stopped in 1998”, “flawed modelling”, “medieval warm period” blah blah blah IF YOU’RE GOING TO DRIBBLE, DO IT INTO YOUR NAPKIN. Whether you love your children, or have trouble chewing, we can all agree that the scariest thing ever has become a bigger snoozefest than Snoozefest 2014, admittedly a poorly conceived event.

Why would most of us rather watch reruns of Dawson’s Creek (I loved when Dawson’s property rights were extinguished by native title), than demonstrably give two hoots about the predicted disintegration of our societies by the end of this century?

The answer, as always, lies in political philosophy.

Guns, Money and Power

Public electoral debate is a tightly controlled spectacle, managed by rival teams of professional experts in the techniques of persuasion, and considering a small range of issues selected by those teams. The mass of citizens plays a passive, quiescent, even apathetic part, responding only to the signals given them. Behind the spectacle of the electoral game, politics is really shaped in private by interaction between elected governments and elites that overwhelmingly represent business interests. Under the conditions of a post-democracy that increasingly cedes power to business lobbies, there is little hope for an agenda of strong egalitarian policies for the redistribution of power and wealth, or for the restraint of powerful interests.

Colin Crouch

So you think you live in a democracy? Well a growing chorus of smart people think you are a rock job. Over the last decade thinkers like Slavoj Zizek, Chantal Mouffe, and Colin Crouch have used terms like post-democracy and post-politics to describe our political situation. This article’s constraints mean the following exposition will have all the precision of a 3 year old scrawling the Louvre’s floor plan with novelty size textas. Nonetheless, how funny are the rubbish drawings of kids?

It doesn't even look anything like the Louvre. Kids Drawings by Scott/cc

Lefty types such as Mouffe are influenced by sometimes great bloke, sometimes book-burning Nazi Carl Schmitt, who in 1927 described the political as a sphere divided into friends and enemies. He noticed two features of liberal democracies, which play hide and seek with this defining feature of politics.

First, we are told there is in fact no division, no friend-enemy split, no viable alternatives to the existing order. Notice the general consensus since the fall of the Berlin Wall that the only way to care for the poor, refugees, our oceans, forests and air, is to work in the derivatives market, because, well, der. Since the halcyon days of Auntie Thatcher and Uncle Rapping Ronnie Reagan, There is No Alternative (TINA) to a neo-liberal nation state and a deregulated capitalist market. There are no great battles of ideas nor inspiring political projects for the future. Thanks to universal human rights and the wonders of the modern market, there is neo-liberal capitalism, forever and ever amen.

Until climate change forces all those without private helicopters to fight to the death in Hunger Games style resource wars.

Schmitt thought the second sneaky trick of liberals was to limit public disagreement to a narrow frame, one contemporary thinkers term post-political. This frame confines debate to ethics and economics and stymies our ability to advocate truly transformational change.

We are consumed with ethical debates around reproductive rights and gay marriage or moral panics about drugs and pornography. We believe recent assertions that the asylum seeker issue is so serious a moral question that it is “beyond left and right”, a claim heard from all three major political parties here in Australia. We are sucked into arguments with the Muppet Brigade who denounce gun control or climate action advocates for insensitively “politicising the issue” in the wake of mass shootings or extreme weather events, when instead they should all be buying AK 47s or lighting forest fires. We tumble in the spin cycle of public ethics, failing to challenge the systemic causes of social and environmental injustice, and unable to even imagine other ways of being in the world.

Our domination by the language of economics functions in a similar way. Governments worship GDP and the insane notion of infinite economic growth. The fundamentals of our globalised market systems are not questioned, or if they are, few viable alternatives are discussed. Instead we waste our breath on the details of the best commodity pricing mechanism to moderate consumer behaviour I’M SO BORED I CAN BARELY FINISH THIS SENTENCE.

Confusing for Republicans and their "Love Guns, Hate Women and Gays" policy platform. awtomat kalaschnikowa by Andreas Schmidt/cc

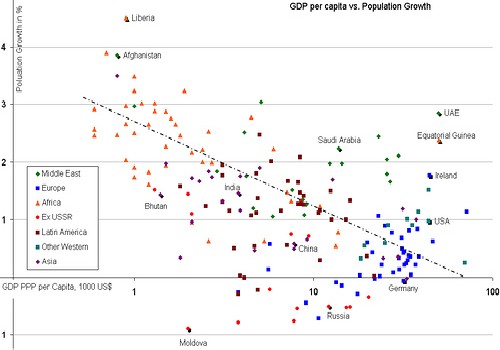

The worst map of the world I've ever seen. Population Growth vs GDP by AtikuX/cc

The issue of climate change is trapped by these same processes, but also indicates how we can get this cheeky post-political monkey off our backs.

Scones, Heroin and the Post-Politics of Climate Change

It is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.

Fredric Jamieson

This is a beautifully crafted statement that rings true, but why? In light of the work of Schmitt and others, the answer is clearer than the high quality lenses you’ll find at Specsavers, now only $99. That’s right, only $99. For over a decade we’ve been bombarded with more nightmare scenarios than customers at your local uncompetitive small business optometrist. We all watched in horror as Al Gore turned a Powerpoint presentation into a feature length film, only to be further devastated by the news that A Really Inconvenient Truth, due in 2014, will exclusively use Excel spreadsheets And we’ve all felt like naughty schoolchildren when in 2006 a top British economist named his whole 700 page report after his severe outlook on the subject.

In the face of graphic imagery of the coming apocalypse (and there is no more graphic sign than Clive Palmer twerking), we’ve been hoping that our political and financial leaders will benevolently decide to be less filthy rich and powerful to avoid catastrophe. Yet expecting the neo-liberal consensus to respond effectively to climate change is like expecting my pet guinea pig Gwen to win the Melbourne Cup. It’s simply not designed for a 3200m race against highly trained thoroughbred horses.

Less grooming, more training champ. Beautiful Bombon! by Jeanie/cc

No chance. Green Moon wins the 2012 Melbourne Cup by SilverStack/cc

Or in the more literal terms of author Naomi Klein in her outstanding piece in The Nation, Capitalism vs the Climate:

Climate change detonates the ideological scaffolding on which contemporary conservatism rests. There is simply no way to square a belief system that vilifies collective action and venerates total market freedom with a problem that demands collective action on an unprecedented scale and a dramatic reining in of the market forces that created and are deepening the crisis.

Klein would agree that over the last two decades the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and has been about as effective in reducing emissions as the UN Framework Convention On Grandma’s Home Made Scones (UNFCGHMS) has been in eradicating the international drug trade.

Way too much heroin to take to Grandma's house. Heroin Drugs Seized by the Counter Narcotics Police of Afghanistan by UK Ministry of Defence/cc

While 97% of political philosophers are unsure about the use of scones, heroin and pet animal metaphors in climate change communication, one named Erik Swyngedow is sure that climate change is dominated by the post-political language of economics and ethics.

Within UNFCCC negotiations between nation-states, scientists, and big NGOs, there has been a longstanding consensus that climate change is real, man-made, and the greatest threat we face. Thankfully we can avert disaster with minor economic adjustments and still be home in time for dinner. Challenges to economic growth and consumerism are neither seen nor heard, nor are ideas for a truly sustainable human existence on this planet. As Swyngedouw argues, “disagreement is allowed, but only with respect to the choice of technologies, the mix of organisational fixes, the detail of the managerial adjustments, and the urgency of their timing and implementation”.

If not framed economically, climate change is framed as a matter of grave moral concern. In 2009 Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd not only often said that climate change is the greatest moral challenge of our time, but also that “climate change is beyond politics”. His advisors did warn the media that Rudd had lost his freaking mind, also saying that playing the 150cc level on Mario Kart was the greatest moral challenge of our time. Nonetheless, even the politicians most passionate about climate action limit their language to the ethical or economic arenas. They do not ask basic questions about the root causes of climate change and so cannot identify effective solutions.

Kevin Rudd as Yoshi, outside the Copenhagen Climate Conference. Mario Kart by trf_Mr_Hyde/cc

Hope for Climate Action?

Activists are caught in the same nauseating cycle. For many years now the flagship campaigns of major NGOs have used the banner of "climate action" to focus on economic mechanisms of climate change mitigation such as an emissions trading scheme or carbon tax. These are disempowering market based forms of climate action which de-emphasise collective struggle. This is exactly the terrain upon which we will always lose to existing constellations of power. Ethics and economics are discourses disposed to the powerful to justify ongoing injustice.

These campaigns fail to articulate clear counter narratives to corporate capitalism and fail to build a broad based social movement which would force global decision makers to decarbonise the global economy. Cognitive linguist George Lakoff once said “in politics, whoever frames the debate tends to win the debate.” So long as we submit to these elite frames for climate action, we will lose. Until we recognise the division at the heart of the political, until we come together as cohesive social groups to build a movement, and until we present inspiring visions of a socially just and sustainable future, we may as well bet on Gwen to come home strong at the Melbourne Cup.

This is the first article in a four part series on the politics of climate change. Episode II spins a rollicking yarn about a warming planet.